By: Adib Bakth

As our ancestors developed their great ancient civilizations (the Mayans, Greeks, Romans, Indians, Chinese, Egyptians, Babylonians, and Arabs), they immersed themselves into the abstract world of math. They played with numbers creating their own unique and sometimes borrowed, numerical systems. They hit milestones of mathematical insight, and learned ways to use their newfound knowledge; applying math to the problems their budding or established societies and civilizations faced, but also, at the same time partaking in uncovering mathematical mysteries for the sake of knowing. All these ancient societies had their notions and workings about and with numbers, but a number of specific has been quite the center of conceptual interest to our ancient mathematicians throughout history; zero. The significance of this concept can't be stressed enough; essentially defining calculus, letting us denote place values with ease, and not to mention, zero's firmly held post as a key to some of the few axioms which must hold true for all legitimate sets of numbers. Zero yields an array of mathematical insight, but how exactly did the concept of zero arise in the crucibles of civilization? What did our predecessors exactly define zero as, and how did they put to use their concepts of this residual value; remaining ever present after we take the average of all numbers, positive and negative.

To understand the upbringings of the notion of zero, we must first take a look at the preserved works of ancient civilizations; placing their mathematical leaps, bounds, and knowledge under a lens of analysis. The conceptual origins of zero arose from the need for a positional value when counting or writing numbers. Thinking of zero as the denotation of a valueless placeholder helped these early civilizations distinguish the difference between numbers like 18, 108, and 180; this notion of zero appeared in civilizations as early as the Mayans and ancient Babylonians (around 5000 years ago). Some of the earliest civilizations, being the Sumerians/Babylonians and ancient Egyptians, had a great need for math. With the settling of these greatly populated and agriculturally based civilizations emerged the need for using math practically; determining taxation, measuring dimensions of crops, as well as other geometric factors pertaining to those crops (such as area and perimeter), counting, calculating, and projecting yields. Having to deal with ever larger numbers bring forth the conceptualization of zero as a placeholder, overall making counting and writing numbers leagues simpler.

The use of zero as a placeholder has been around since, essentially, the crucible of humanity and civilization; since our race first shifted from a nomadic hunter gatherer lifestyle, settling down into ever expanding groups and societies cultivating the land. This primitive notion of zero is a good start, conceptually, but the mathematical insight this number holds has the potential to unlock so much more underlying mathematical understanding. Dealing with zero as a number in its own regard, a mathematical abstraction that can be used as a tool for uncovering further mathematical knowledge rather than merely a placeholder, is the next leap forward in the history of math. Some of the earliest records of zero being used as a placeholder dates back to the 3rd or 4th century in the subcontinent of India. The ancient Indians were prolific users of math, delving into this world for, sometimes, more than just practical reasons; for true insight into the abstract world that math forges on paper.

The Indians viewed zero as a number itself, and this can be seen from reading what their civilization has left behind. Discovered by a Pakistani farmer, the Bakhshali manuscript displays the mathematical knowledge these ancient Indians could conceptually yield. It is composed of worked examples and problems that they were able to proficiently solve at the time. In this manuscript is another example of zero showing up as a placeholder; yet the Indians would soon take the place holding dot leaps and bounds further. The dots found scattered throughout the manuscript would one day evolve into the hollow centered ring we call zero today. Brahmagupta, Indian mathematician and astronomer, would go on to detail zero as a concrete number in its own regard in his later works, dated to around 628 AD. His preserved works display that he was delving into a world of negative numbers, and worked out addition and subtraction between 0, positive, and negative numbers. His attempts to detail the case of division by 0 yielded inconclusive results, but his conceptual leap would live, evolve, and thrive; conquering entire areas of math we utilise today.

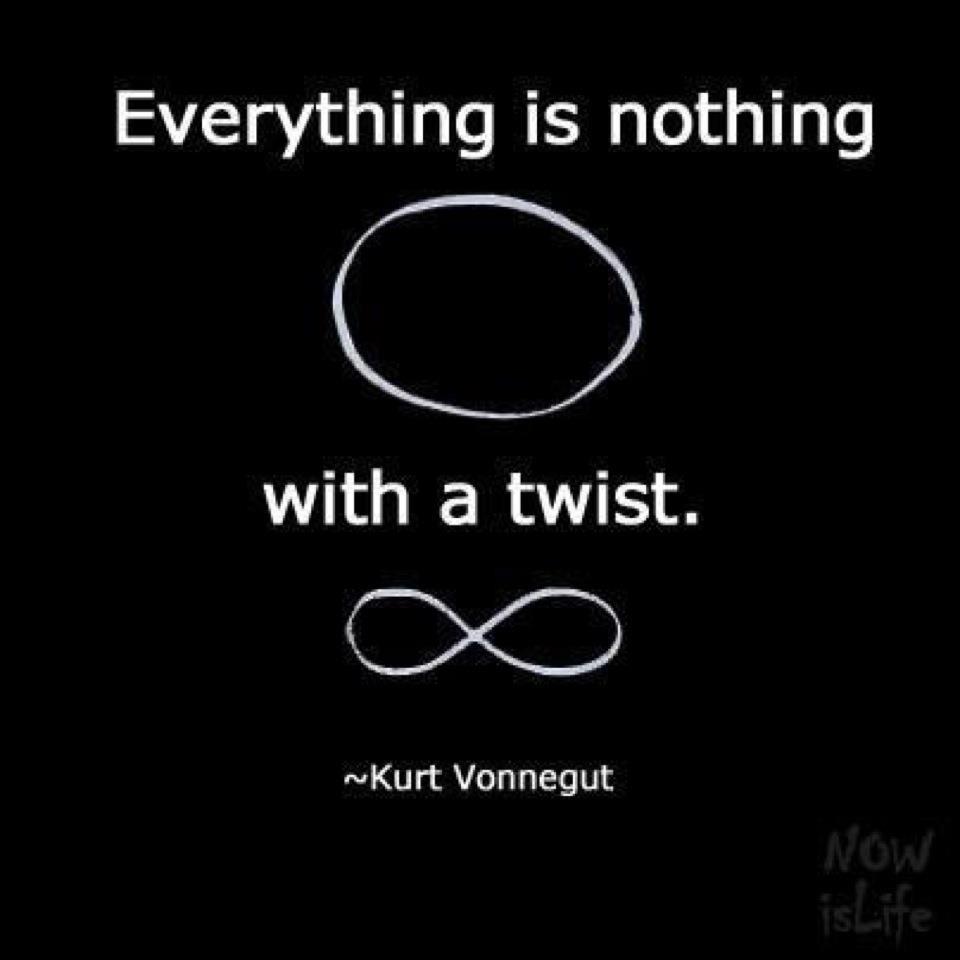

So many of our ancients had their concepts of zero, which they independently arrived to, all be it merely as a placeholder. What the Indians did though was take the concept of zero infinite steps forward; we take zero for granted, especially so the willingness for our race to have even cared about zero and its properties. Who could blame the peoples of these primitive civilizations for not embracing a number denoting no value at all? After all, what use is there of a number representing the absence of value in a practical sense. Being such an abstract conceptual leap, it's easy to see why many of our ancients could never bother making it. Yes, zero is a key, unlocking the door to a world of amazing perplexity, but only if you know how to traverse the highly tricky mathematical terrain surrounding it. Indeed, zero unlocks calculus, insight into infinity, as well as of course the negative spectrum of numbers spanning to negative infinity, and so much more; to such early peoples though, with a vastly limited knowledge of the abstract world we call math, in comparison to us and all we know now, what would be the sense in delving into this conceptual representation of nothing? Especially so when the practical uses of such a concept would seem as non existent as the number in question itself? Who could have ever guessed zero unlocks the world of understanding we now realise it provides?

The Indians, working with this abstract notion of zero as a number in and of itself, could have never predicted what vast insight this conceptualisation would yield mathematically, but they were definitely culturally equipped to give the void meaning; they holstered a cultural openness and longing to understand the void that, essentially, no other ancient civilizations possessed. A mixture of intellectual soul searching and a cultural openness to the idea of nothing gave rise to a tool that would go on to revolutionise math, its practical uses, and ability to describe the very fabric of reality itself. Many mathematicians consider the conceptual leap of viewing zero as a number as one of the single greatest mathematical advancements in history, and it's very hard to argue the opposite view; considering all zero has given us access to.

Being conceived in Southern Asia, the representation of nothing as a number travelled across the arab world, eventually finding itself knocking at the doors of European civilizations. With every civilization having their own, or similar/shared/mutual, mathematical systems in order, the acceptance of the notion of a number for nothing was obviously neglected. Being such an abstract way to think about a number, the interests and incentives for delving into the mathematical denotations and connotations of such a number were clearly low. Despite this, the ancient civilizations of the time (the ancient arabic world as well as Greeks, Romans, and some African civilizations, Egyptians being a big one) at least build familiarity with the notion of zero as a distinct number, though not fully compelled to embrace it and all it's mathematical holiness just yet.

The winds of time always stir change, and as these budding civilizations developed, expanded, and in cases even toppled, long standing cultures, societies, as well as ideologies wavered and evolved. With time, many of the hindering factors to scientific and intellectual advancement, eventually, were shoved out of the way; the passage of time paved a path for insightful mathematical as well as scientific understanding, directly resulting in ever more practical applications and real life manifestations of the two. As our race delved into an abstract world, we found ways to pull practicality from the pages themselves; math unlocked a world of understanding. Math gave us a tool to understand how everything ticks and the understanding zero was, arguably, one of the first and most important bounds into this abstract world we ever took; unlocking a universe of understanding.

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cZH0YnFpjwU https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/history-of-zero/ https://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Zero.html https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQEuywkWa2U https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Y7gAzTMdMA https://malini-math.blogspot.ca/2010/03/zero.html https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-41265057?SThisFB https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-oxsEknlIc&feature=share https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pV_gXGTuWxY&feature=share https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/sep/14/much-ado-about-nothing-ancient-indian-text-contains-earliest-zero-symbol