By Adeeb Chowdhury

The path to gender equality in Bangladesh is a long, winding, and difficult path. It is a path marred by anti-equality laws and scarred by traditional family roles, especially in rural areas. These "traditional" roles are the toxins poisoning the bloodstream of the feminist movement across the nation—these roles are what is handicapping the empowerment of girls. Young girls in villages are denied access to education and economic responsibility, virtually terminating any opportunity of success or innovation in life. As the renowned author and activist Christopher Hitchens noted, "the cure for poverty is often the empowerment of women"—liberating women from the shackles of forced marriage and allowing them to seek out their own future, establish their own success. This is one of the objectives of the modern gender equality movement, and always has been, because the social oppression and repression of women deprives humanity of much of its innovation, creativity, hope, and potential. Child marriage handicaps the future of young girls in Bangladesh and across the world. It robs them of their education and training for life. It often imposes early pregnancy and childbirth upon them, leading to possible health defects and medical complications. Girls trapped in early marriages are often subjected to domestic violence if unwilling to cooperate.

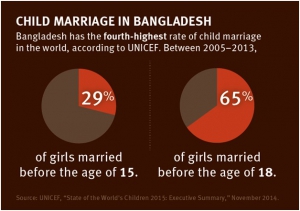

Though the plague of child marriage is present almost worldwide, it is especially endemic in rural Bangladesh. According to UNICEF, this country has the highest rate of child marriage of young women under the age of 15 in the world, with 29 percent of girls in Bangladesh married before this age. This reflects a horrifying underlying mindset present in this nation—the poisonous mindset that girls are viewed as objects to be traded and profited from, rather than a source of potential economic success by themselves. Parents see this as relieving themselves of a "burden"—since the girl clearly cannot do well in school or earn money, cooking and cleaning and having children must be what they are good for. To make matters worse, families hope to gather money from dowry by selling their girls off to get married, although this practice is internationally condemned and outlawed. The situation in Bangladesh was worsened when on February 27, 2017, the Parliament approved a new law allowing child marriage (under 18) "under special circumstances." This is very vaguely defined, and can be exploited quite easily. "The focus now must be on containing the damage caused by Bangladesh legalizing child marriage. Nothing can change the fact that this is a destructive law. But carefully drafted regulations can mitigate some of the harm to girls," said Heather Barr, senior researcher on women's rights at Human Rights Watch. But, there is a new revolution sweeping the countryside of Bangladesh—the power of teenagers. UNICEF has recently opened almost 6000 youth centers across the country. These centers educate and empower both young men and women, promoting gender equality and social progress. This has spurred numerous youthful Bengalis to campaign against child marriage, seeing the visibly destructive effects. This is the theme of an intriguing new report by the site Broadly, investigating this new teenage revolution. The report describes the work of Dipko, a 17-year-old Bengali in a Sylheti village. Dipko reported that he was influenced enormously by the UNICEF youth center he attended, learning about the pitfalls of child labor, child marriage, and lack of basic child rights. He was inspired to translate this message into action, gathering his friends and making a plan for combating the prevalence of child marriage. "We learned we have rights and how it's not only bad for girls because they don't go to school, but can hurt their health if they have babies before their bodies are really ready," Dipto stated in an interview. "Once I understood how bad it was, I felt like I had to do something." Dipko takes it upon himself to travel around the villages, knocking on strangers' doors and promoting the idea of child rights and women empowerment. His aim is to have a frank conversation with them, trying to convince them to help stop early marriages in their vicinity. "Lots of parents tell me to mind my own business, that it is their child and their choice. In response, sometimes I threaten to bring the police." He also described how he had received a number of threats of physical assault from various families who weren't fond of his teachings. Another bright example is the story of 17-year-old Laxmi, a Bengali village girl born with a disability that made it physically painful to walk or engage in strenuous physical activity. She too was inspired by the messages of the UNICEF youth center, enlightened by the idea that she herself had basic human rights that should be upheld—which is often an alien idea in some parts of Bangladesh.

When she found out that her parents were considering marrying her off, she did not hesitate to protest. She refused to budge, absolutely entrenched in her defense of her own rights. When her parents confronted her and pointed out that the dowry would help her impoverished family, she had a dazzling reply—she learned how to sew. She created fabric and saris, and now her work is bringing in money to help her siblings. "I am not against getting married one day, but now I get to choose who, and when," were her memorable words. Recently, a teenage activist against child marriage received the prestigious International Woman of Courage (IOWC) Award by US First Lady Melania Trump. Sharmin Akter was forced by her mother at age 15 to be wedded to a stranger. But she fought back, combating her parents' efforts and successfully bringing her mother and her to-be husband to justice. According to the US State Department, Sharmin "demonstrated exceptional courage and self-possession" and "dared to break the silence expected of women and girls and advocated for her rights". Sharmin voiced her intentions to later study law and work to reverse Bangladesh's regressive practice of child marriage. Laxmi, Dipko, Sharmin are only a handful examples of the leaders of the teenage revolution sweeping across rural Bangladesh. It is enlightening and utterly inspiring that the new generation of Bengalis is not intimidated by progressive ideas—in fact, they embrace them, and they fight for them. It is refreshing to find that at least part of this country is bravely flowing forwards instead of creeping backwards.

Sources • https://broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/the-teens-going-door-to-door-to-stop-child-marriages?utm_source=broadlytwitterus • https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/02/bangladesh-legalizing-child-marriage-threatens-girls-safety • https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/06/09/bangladesh-girls-damaged-child-marriage